Davenport–Schinzel sequence

In combinatorics, a Davenport–Schinzel sequence is a sequence of symbols in which the number of times any two symbols may appear in alternation is limited. The maximum possible length of a Davenport–Schinzel sequence is bounded by the number of its distinct symbols multiplied by a small but nonconstant factor that depends on the number of alternations that are allowed. Davenport–Schinzel sequences were first defined in 1965 by Harold Davenport and Andrzej Schinzel to analyze linear differential equations. Following Atallah (1985) these sequences and their length bounds have also become a standard tool in discrete geometry and in the analysis of geometric algorithms.[1]

Contents |

Definition

A finite sequence U = u1, u2, u3, is said to be a Davenport–Schinzel sequence of order s if it satisfies the following two properties:

- No two consecutive values in the sequence are equal to each other.

- If x and y are two distinct values occurring in the sequence, then the sequence does not contain a subsequence ... x, ... y, ..., x, ..., y, ... consisting of s + 2 values alternating between x and y.

For instance, the sequence

- 1, 2, 1, 3, 1, 3, 2, 4, 5, 4, 5, 2, 3

is a Davenport–Schinzel sequence of order 3: it contains alternating subsequences of length four, such as ...1, ... 2, ... 1, ... 2, ... (which appears in four different ways as a subsequence of the whole sequence) but it does not contain any alternating subsequences of length five.

If a Davenport–Schinzel sequence of order s includes n distinct values, it is called an (n,s) Davenport–Schinzel sequence, or a DS(n,s)-sequence.[2]

Length bounds

The complexity of DS(n,s)-sequence has been analyzed asymptotically in the limit as n goes to infinity, with the assumption that s is a fixed constant, and nearly tight bounds are known for all s. Let λs(n) denote the length of the longest DS(n,s)-sequence. The best bounds known on λs involve the inverse Ackermann function

- α(n) = min { m | A(m,m) ≥ n },

where A is the Ackermann function. Due to the very rapid growth of the Ackermann function, its inverse α grows very slowly, and is at most four for problems of any practical size.[3]

Using big O and big Θ notation, the following bounds are known:

- λ1(n) = n.[4]

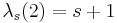

- λ2(n) = 2n − 1.[4]

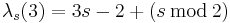

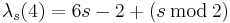

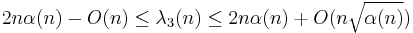

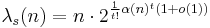

.[5] This complexity bound can be realized to within a constant factor by line segments: there exist arrangements of n line segments in the plane whose lower envelopes have complexity Ω(n α(n)).[6]

.[5] This complexity bound can be realized to within a constant factor by line segments: there exist arrangements of n line segments in the plane whose lower envelopes have complexity Ω(n α(n)).[6]- For even values of s ≥ 4,[7]

-

, where t = (s − 2)/2.

, where t = (s − 2)/2.

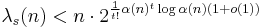

- For odd values of s ≥ 5 the best known upper bound is [7]

-

, where t = (s − 3)/2.

, where t = (s − 3)/2.

However, this bound is not known to be tight.[7]

The value of λs(n) is also known when s is variable but n is a small constant:[8]

Application to lower envelopes

The lower envelope of a set of functions ƒi(x) of a real variable x is the function given by their pointwise minimum:

- ƒ(x) = miniƒi(x).

Suppose that these functions are particularly well behaved: they are all continuous, and any two of them are equal on at most s values. With these assumptions, the real line can be partitioned into finitely many intervals within which one function has values smaller than all of the other functions. The sequence of these intervals, labeled by the minimizing function within each interval, forms a Davenport–Schinzel sequence of order s. Thus, any upper bound on the complexity of a Davenport–Schinzel sequence of this order also bounds the number of intervals in this representation of the lower envelope.

In the original application of Davenport and Schinzel, the functions under consideration were a set of different solutions to the same homogeneous linear differential equation of order s. Any two distinct solutions can have at most s values in common, so the lower envelope of a set of n distinct solutions forms a DS(n,s)-sequence.

The same concept of a lower envelope can also be applied to functions that are only piecewise continuous or that are defined only over intervals of the real line; however, in this case, the points of discontinuity of the functions and the endpoints of the interval within which each function is defined add to the order of the sequence. For instance, a non-vertical line segment in the plane can be interpreted as the graph of a function mapping an interval of x values to their corresponding y values, and the lower envelope of a collection of line segments forms a Davenport–Schinzel sequence of order three because any two line segments can form an alternating subsequence with length at most four.

See also

Notes

- ^ Sharir & Agarwal (1995), pp. x and 2.

- ^ See Sharir & Agarwal (1995), p. 1, for this notation.

- ^ Sharir & Agarwal (1995), p.14.

- ^ a b Sharir & Agarwal (1995), p.6.

- ^ Sharir & Agarwal (1995), Chapter 2, pp. 12–42; Hart & Sharir (1986); Wiernik & Sharir (1988); Komjáth (1988); Klazar (1999); Nivasch (2009).

- ^ Sharir & Agarwal (1995), Chapter 4, pp. 86–114; Wiernik & Sharir (1988).

- ^ a b c Sharir & Agarwal (1995), Chapter 3, pp. 43–85; Agarwal & Sharir (1989); Nivasch (1999).

- ^ Roselle & Stanton (1970/71).

References

- Agarwal, P. K.; Sharir, Micha; Shor, P. (1989), "Sharp upper and lower bounds on the length of general Davenport–Schinzel sequences", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series A 52 (2): 228–274, doi:10.1016/0097-3165(89)90032-0, MR1022320.

- Atallah, Mikhail J. (1985), "Some dynamic computational geometry problems", Computers and Mathematics with Applications 11: 1171–1181, doi:10.1016/0898-1221(85)90105-1, MR0822083.

- Davenport, H.; Schinzel, Andrzej (1965), "A combinatorial problem connected with differential equations", American Journal of Mathematics (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 87 (3): 684–694, doi:10.2307/2373068, JSTOR 2373068, MR0190010.

- Hart, S.; Sharir, Micha (1986), "Nonlinearity of Davenport–Schinzel sequences and of generalized path compression schemes", Combinatorica 6 (2): 151–177, doi:10.1007/BF02579170, MR0875839.

- Klazar, M. (1999), "On the maximum lengths of Davenport–Schinzel sequences", Contemporary Trends in Discrete Mathematics, DIMACS Series in Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science, 49, American Mathematical Society, pp. 169–178.

- Komjáth, Péter (1988), "A simplified construction of nonlinear Davenport–Schinzel sequences", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series A 49 (2): 262–267, doi:10.1016/0097-3165(88)90055-6, MR0964387.

- Mullin, R. C.; Stanton, R. G. (1972), "A map-theoretic approach to Davenport-Schinzel sequences.", Pacific Journal of Mathematics 40: 167–172, MR0302601, http://projecteuclid.org/getRecord?id=euclid.pjm/1102968831.

- Nivasch, Gabriel (2009), "Improved bounds and new techniques for Davenport–Schinzel sequences and their generalizations", Proc. 20th ACM-SIAM Symp. Discrete Algorithms, pp. 1–10, arXiv:0807.0484, http://www.siam.org/proceedings/soda/2009/SODA09_001_nivaschg.pdf.

- Roselle, D. P.; Stanton, R. G. (1970/71), "Some properties of Davenport-Schinzel sequences", Acta Arithmetica 17: 355–362, MR0284414.

- Sharir, Micha; Agarwal, Pankaj K. (1995), Davenport–Schinzel Sequences and Their Geometric Applications, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-47025-0.

- Stanton, R. G.; Dirksen, P. H. (1976), "Davenport-Schinzel sequences.", Ars Combinatoria 1 (1): 43–51, MR0409347.

- Stanton, R. G.; Roselle, D. P. (1970), "A result on Davenport-Schinzel sequences", Combinatorial theory and its applications, III (Proc. Colloq., Balatonfüred, 1969), Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 1023–1027, MR0304189.

- Wiernik, Ady; Sharir, Micha (1988), "Planar realizations of nonlinear Davenport–Schinzel sequences by segments", Discrete & Computational Geometry 3 (1): 15–47, doi:10.1007/BF02187894, MR0918177.

External links

- Davenport-Schinzel Sequence, from MathWorld.

- Davenport-Schinzel Sequences, a section in the book Motion Planning, by Steven M. LaValle.